The Tongariro Crossing is the most popular tramp in the country. In the winter however the crowds lessen when the slopes are covered in ice and snow, and crampons + ice axe are needed to make it across. A massive, but amazing, trip – if you have the right weather for it.

Length: 19.4km one-way trip, including a 1,196m change in elevation

Time taken: Spoiler alert – we didn’t make it all the way across this attempt

Difficulty: Difficult – in winter I would highly recommend guides for anyone inexperienced or unconfident in winter alpine conditions.

Facilities: There are toilets (without paper) peppered along the track. The longest break is right in the middle of the tramp. Check out the map on this brochure. Running and still water in the Park is not safe to drink. This is due to the high levels of dissolved minerals from the volcanic rock it passes through on its way to the surface. However up higher there’s usually plenty of freshly fallen snow to melt down.

– Important: This is a very exposed alpine tramp involving high fall/slide and avalanche risks, as well as very changeable weather conditions. Do not attempt if the weather isn’t favourable, if the avalanche risk is high, or if you are not confident in this kind of terrain. In winter, helmet, crampons and ice axe (and the knowledge to safely use them) are mandatory. –

Why tramp the Crossing in winter?

Having only moved to the North Island earlier in the year, I hadn’t yet had the chance to tackle the famous Tongariro Crossing. But I dearly wanted to. I didn’t have any winter alpine experience. I could count on one hand the number of times I’d walked with crampons. And I hadn’t ever picked up an ice axe before). So I’d never even considered climbing it in winter – that was until I won a competition (thanks Macpac!) to go on a trip with Got to Get Out and Adrift Tongariro Guides! My friend Grace (who had climbed up to Mueller Hut with me three years prior) came along as well. We unfortunately didn’t make it all the way across on this first attempt. But did have a bit of an adventure (more on that further down). We were determined however to complete it, so Grace and I returned a month later with another guiding company; Adventure Outdoors, and this time, with perfect weather, we made it all the way! You can check out a trip report from that adventure here.

How to get there?

The Tongariro Crossing is a one-way trip – so you’ll need to sort out transport. There are plenty of shuttles that you can book online. Or you can drop off a car at either end (at the time of writing, the 4 hour parking restriction only applies during the summer season; October – April). However if you’re doing a guided trip (which I would highly recommend in winter if you haven’t got the necessary experience), then the cost includes return transport either from National Park (Adrift), or from your accomodation (Adventure Outdoors). If you’re staying in Turangi or Taupō, the two guiding companies also go that far out, but it’s more expensive and means a much earlier wake-up call.

The Crossing is usually walked from Mangatepopo carpark on the West, to Ketetahi carpark on the North. This means you get significantly more descent than ascent over the course of the day. To get to Mangatepopo carpark, take SH47 from National Park or Turangi and turn on to Mangatepopo Rd, drive 10 min down the narrow road (careful of oncoming traffic around blind corners), before dead-ending at the carpark and the start of the Crossing!

First Attempt – July, Adrift guides

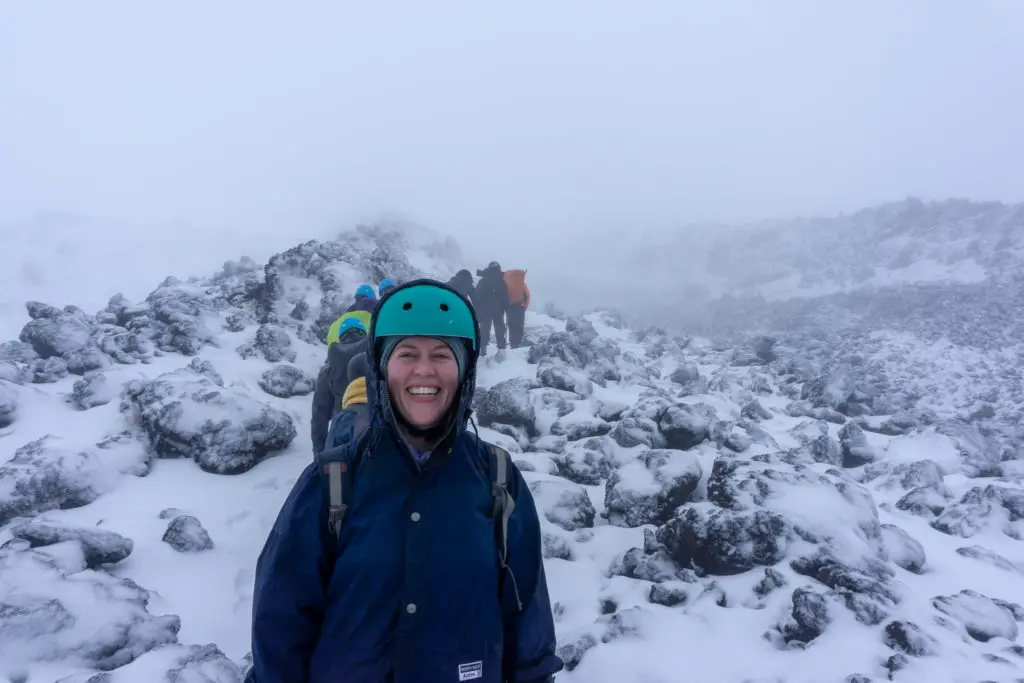

The weather wasn’t looking good and our guides gave us a 50/50 chance of actually making it all the way across. But they were still going to take us up. It would be the 65km+ winds on Red Crater ridge that would likely stop us, but we were all keen to give it a go (buoyed by our naive optimism). At their office in National Park, our guides did a very quick perusal of our gear, fitted our crampons, gave us ice axes and helmets. Then we were loaded onto the bus, rearing to go!

Grace and I ended up in the van behind the bus. Our insanely positive driver chatted happily away about how bad weather was actually quite a good thing – it forces you to pay attention to the many beautiful features of the Mangatepopo Valley rather than staring awestruck at Mt Ngauruhoe the whole time (true). He also was of the opinion that we might get to South Crater and actually find that the wind wasn’t as bad as had been predicted. We might even get some views (false, as it turned out). I looked out the steamed up window as we drove up Mangatepopo Rd and all I saw was fog and cloud. My optimism wavered slightly.

We arrived at the carpark, hopped out of the van, listened to a quick briefing about how to carry the ice axe on our packs, and then set off. The Got to Get Out group was quite big, so the going was slow. I didn’t mind, it was the first time Grace and I had caught up since she’d arrived back in New Zealand after two years teaching English in Korea, so we had a lot to talk about as we walked up the valley.

Devil’s Staircase

After about 1.5 – 2 hours of walking (wearing gloves and the freezing weather meant that I didn’t reliably look at my watch) we arrived at the last set of toilets before the craters. Snow and ice had started to appear on the ground in patches. As we climbed up the Devil’s Stairase, it felt like we were climbing into a different world. I would have already turned back by this point if I had been travelling without guides. In all honesty, I would have looked at the forecast and not even attempted the trip). So every step was a new experience. The wind started to pick up. Soon people’s pack covers were acting like parachutes and everyone had a bit of a lean. We’d taken our ice axes out for safety, but ended up using them as walking sticks to help manage the wind and ice.

The Staircase felt like it took forever. Partly because our guide in front had the hard work of cutting the ice away from the stairs. So every few steps we stopped for a rest, while he was up front swinging his ice axe. The higher up we got, the worse the conditions were. Soon when there was a wind gust, it looked as though the front of our line had been swallowed by a white monster of rain, ice and snow. I’d never been in conditions like this before (mainly because I’d never felt safe putting myself into a situation like this before), and it was certainly an exhilarating experience!

South Crater

As we turned the corner into the relative shelter of South Crater, the wind abated slightly. The guides asked us if we were all happy to keep going ahead. I was really keen, however a few people told me afterwards that they were cold and nervous, but felt like they couldn’t say anything in front of the group, so kept their mouths shut. The power of peer pressure!

No-one from our group turned back, and we kept going through South Crater to the bottom of Red Ridge. I know now that beautiful Ngauruhoe would have been off to our right, and Tongariro to our left, but the visibility was so poor that I had no clue – we could barely see the front of the single-file line. I had to rely on Grace’s narration (she’d done the tramp a few years ago in summer) about what I would normally be seeing. It only made me determined to return with good weather.

Red Ridge

At the bottom of Red Ridge, we put on our crampons with the guides’ instructions. They weren’t too sure about taking us all up to the ridge. Particularly as we knew we’d just be coming back down again – with the conditions it was too unsafe to even consider going on along the narrow ridge. But in the end, the head guide and owner of Adrift, Stew, decided it was ok. We headed slowly on up, testing out walking with our crampons for the first time. Looking back, and knowing what the drop-offs are either side (you couldn’t see much that day due to the wind and snow/ice), I now don’t really feel comfortable having gone up there in those conditions without having been taught how to safely stop if I slid (we were told to keep our ice axe in our uphill hand, but self-arresting wasn’t mentioned). When we got to the top, the wind was so strong we had to really dig in all points of the crampons and hold on to the ice axe to not be blown off our feet and off the ridge. We quickly turned back around again and headed down.

Then things got dicey

The wind halved in ferocity once we reached the floor of the crater. My hands, which had been stinging very painfully in the wind through my prolyprop gloves – especially the uphill hand holding onto the freezing metal ice axe, had since lost feeling. I was very grateful to reach the bottom, put my ice axe away and put my hands into my pockets to warm up. It just shows my relative inexperience in winter alpine conditions (and the casual perusal of our gear by the guides) that I went up in those conditions without waterproof gloves. Although even people with waterproof gloves said their gloves were soaking as well due to the relentless icy wind and sweat from the climb up.

Everyone was looking a little worse for wear, hunched up against the wind. We quickly got started again, retracing our steps across the crater, but this time facing into the wind. Grace and I hung back so we could selfishly shelter behind the majority of the group. When I looked back to check on the people behind us about 2/3 of the way through the crater, I noticed that one of the ladies from our group was being supported by two of her friends, although she was still walking. They waved us on when we stopped to ask if she was ok. When I looked back a few minutes later she was lying on the ground 20m back, surrounded by the last of the group and the tail-end guide.

We all halted, almost at the edge of the crater, as the guides reacted quickly. They erected a temporary windproof shelter around her, gave her extra layers of clothing and more food and fluids. Her sister even chewed up a very cold and hard Snickers bar and popped it into her mouth to give her some energy without any expenditure (when I tell that story, people either think it’s incredibly loving or extremely gross). It’s unclear what exactly happened, but she’d apparently arrived back from China no more than a week before doing the Crossing and hadn’t been feeling well the day before. It was extremely cold, at a high altitude. She likely hadn’t been eating or drinking as much as normal because of the conditions. Nobody wanted to take their bags and gloves off to rummage around in their bags for food and drink when it was so windy and cold.

While I hadn’t been feeling uncomfortable at any point up until now, I quickly realised how precarious a position we were in. We were over 3 hours up the mountain, in terrible conditions, with an almost unconscious person lying on the snow and a large group of people of varying levels of skill, confidence and gear. Even with a personal locator beacon (PLB), which I carry, there was no chance of any helicopter pilots even thinking about taking off in these conditions. Land response time would have been more than 3 hours. It really made me appreciate how quickly things can go from fine to really bad. And how carrying a PLB isn’t a magic wand. In instances like this, if you were travelling alone, setting off the PLB wouldn’t help LandSAR find you, it would help them find your body.

After much deliberation, the guides eventually decided to split the group; the majority of people would head down with one guide in front and one at the back. A smaller group of strong volunteers stayed behind to help the other two guides carry the sick lady off the mountain. Unfortunately because of my gloves and hands, which were still pretty dicey, I felt like I’d be more of a hinderance than a help if I stayed behind, so Grace and I went down with the first group. It felt very, very wrong to be turning my back and walking away from someone lying on the snow. The guides got our group off the mountain very quickly once the decision was made, and stayed in radio contact with the group we’d left behind. They let us know that the lady had perked up and was walking out mostly unassisted, which made us all breathe a sigh of relief. In the end, they were only 45 minutes behind us. The situation must have turned back around almost as quickly as it had gone pear-shaped.

Final thoughts

That night back at the lodge, our big group shared wine and stories in front of a roaring fireplace. The lady who’d been unwell was feeling a lot better, but thought the better of indulging in any drinks that evening. One guy talking about how if it wasn’t for the large size of the group, he thought we would have definitely made it all the way across. I listened incredulously as the rest of his group agreed; I still don’t understand how they arrived at that conclusion. They must have forgotten what it felt like to stand on that ridge. The guides had even said to anyone who asked that there was no way they would have attempted the full Crossing in those conditions, let alone led a group of inexperienced trampers over. My take-away from the experience was completely the opposite; instead of feeling bravado and confidence, I felt a deepened respect for the mountains and weather conditions, and how they bow to no-one’s wishes.

All up, despite a failed attempt at completing the Crossing, my July trip was an amazing experience that I was very grateful to have had. I met some awesome people from Got to Get Out. It was inspiring to see so many people getting out and experiencing nature at her wildest. I was determined to complete the winter Crossing, and with views this time! My adventure wasn’t over.

If you want to read about what happened on our second attempt a month later (and much better photos), check it out here.

Safety

As always, please stay safe when you’re out exploring. Follow the Outdoor Safety Code:

- Choose the right trip for you (read my article on tramping safety, speak to DOC)

- Understand the weather (including avalanche advisory)

- Pack warm clothes and extra food (check out my post here about what gear you need to take). In winter you will need crampons, ice axe and helmet – and guides if you’re not experienced or confident.

- Share your plans and take ways to get help (have an emergency beacon on your person)

- Take care of yourself and each other

If you’re not feeling super confident then you can always get in touch with me here on the blog or on my Instagram. Or take a look at my Tramping 101 series which includes this post about how to stay safe in the outdoors.

Also don’t be a dick, check out my guide to New Zealand tramping etiquette.

Stay safe and get outside!