These two tramping rescue stories mirror each other, decades apart. When I first heard the evolving news story of Pavlina and Ondrej, it sent shivers down my spine. Their story has eery similarities to another rescue story in the exact same place almost 30 years earlier, witnessed by my parents. Both of them are explored down below, read on!

Tramping Rescue Story: A month trapped and alone

July – August 2016, Routeburn Track

On August 24, 2016 the New Zealand media reports that a Czech woman has been rescued from Lake Mackenzie Hut on the Routeburn Track. Initially all that is known is that her and her partner hadn’t made contact with their families since July, and that her partner is unaccounted for, presumed dead.

What follows is a bit of a media storm in our small country. Not many people remain stuck in the New Zealand wilderness for that long without the alarm being raised. The general public had a lot of questions.

Here are the chain of events that have since been made public:

July 25, 2016

Pavlina Pizova and Ondrej Petr, two Czech tourists on holiday visas in New Zealand, drive to the Routeburn Shelter carpark. They spend the night in their van. After having completed a few walks in the Queenstown area, they plan on tackling the Routeburn Track and walking back out via the Caples Valley.

The couple had previously sought advice from DOC in Queenstown. The staff warned them not to complete the track in winter conditions. They have not told anyone of where they are going, or when they should be expected back. They checked the weather, but failed to account for the poor alpine forecast.

July 26, 2016

Pavlina and Ondrej set off to Falls Hut. They encounter a few people on the track up to Falls, but are the only ones in the hut that night. They do not take a PLB, ice axe, crampons, or a tent. The couple do not write their names or intentions in the DOC visitor book, wanting to avoid paying the hut fees.

July 27, 2016

By 10am, Pavlina and Ondrej start the climb up and over Harris Saddle to Lake Mackenzie. In summer this is signposted as a 1-2 hour climb, but the Czech couple encounter heavy snow conditions. It takes them 5 hours to reach the shelter at Harris Saddle.

The next part of the Routeburn Track to Lake Mackenzie is signposted as 3 hours in summer. The track crosses numerous avalanche paths (as does the part of the track they’d just completed from Falls Hut). Instead of turning back, or spending the night at the basic shelter at Harris Saddle, they make the decision to continue on.

As night falls, the weather deteriorates. There is a blizzard with only a metre or so of visibility under the light of their headlamps. Pavlina and Ondrej lose track of the trail markers, and then come across their own footprints. They’ve been walking around in circles in the snow and dark.

They take shelter near a rock face, but because they have no emergency shelter, they spend a fraught night in sodden sleeping bags. Pavlina says she couldn’t sleep, fearing they would be buried by the snow that was still falling heavily.

July 28, 2016

The day dawns and the weather is much clearer. Both Pavlina and Ondrej are “blue” with cold, and Ondrej was starting to show signs of hypothermia. They can see that Mackenzie Hut is “very close” and decide to skip breakfast, thinking they can eat and drink when they reach the safety and warmth of the hut.

There is heavy snow on the track that zig-zags down to the lake. Pavlina and Ondrej also know that there are avalanche paths crossing it, so they decide to take a “shortcut” heading straight down to the hut. They head off the track and become lost below the bush-line.

The weather deteriorates again. Ondrej starts to have “trouble with his trousers”, so he takes them off. Pavlina tries to climb up and find the track, leaving Ondrej sheltered under a rock with some food. When she rejoins Ondrej, he has taken off his puffer jacket (saying it was “too heavy”) and swapped to a lighter soft shell jacket.

As they continue on, now in darkness, Ondrej becomes more and more hypothermic. His voice changes, he says “weird stuff” that Pavlina can’t understand, and starts biting wood. Suddenly the pair slip, the snow giving way beneath them. Ondrej is trapped and Pavlina can’t get him out; afraid that if she tries to move him, he’ll fall through the branches trapping him and slip further down the steep mountainside. She listens to him taking laboured breaths, until she realised he has stopped breathing.

Pavlina reaches Ondrej and checks his pulse, nothing. She stays with Ondrej that night.

July 29, 2016

Pavlina manages to grab a few items from Ondrej’s backpack, including a headlamp as hers was lost in the fall. She lays out Ondrej’s black jacket on the shrub to help mark his location, before climbing back up to where they had fallen, where she finds her pack. She boils some water and eats some food.

Pavlina finds the track and tries to follow the markers, but becomes lost. She has lost both of her gloves and fog has set in. Pavlina realises she won’t reach the hut today. It snows heavily again that night.

July 30, 2016

Mackenzie Hut is visible further down the valley. Pavlina heads straight towards the lake, and then traverses around the shoreline to reach the hut. Large boulders make the going difficult, and Pavlina falls into the half-frozen lake at one point. She finally reaches Lake Mackenzie Hut just after midday.

Pavlina breaks into the wardens quarters where she subsists on meager rations. There is a radio, but Pavlina doesn’t know how to work it and can’t decipher the English instructions.

Pavlina fashions snow-shoes from old crates, but she hears avalanches coming down all around her, and knows there are several that cross the track between Lake Mackenzie and the end of the track at the Divide. She tries at least once to walk out, but her physical and mental state makes it too dangerous and she turns back to await rescue.

And waits. For 25 days she waits. She writes a diary. She draws an “H” for help in the snow using ashes from the fire. No other trampers visit the hut. Pavlina waits.

Back home in Czechia, family post in a facebook group, asking if anyone has heard from Pavlina or Ondrej. The Czech Republic Honorary Consul sees this message and raises the alarm with NZ Police. Emergency services find their dusty vehicle in the Routeburn Shelter carpark, and from there they mount a rescue / recovery effort along the Routeburn Track.

August 24, 2016

Pavlina is spotted by a helicopter, waving out the front of Mackenzie Hut. She is ecstatic to be rescued, and in a relatively good condition, all things considered. From the helicopter, she points out where Ondrej lies.

August 26, 2016

The body of Ondrej Petr is recovered from near the Routeburn Track above Lake Mackenzie, a full month after he left the Routeburn Shelter carpark.

August, 2016

Pavlina gives a “four figure” donation to DOC and LandSAR as recognition for their efforts in her rescue. She returns home to Czechia.

Learnings

The Mountain Safety Council described the following recommendations for trampers based on this story (quoted from the Coronial Findings for Ondrej Petr, linked below):

- Before heading off on any adventure, discuss and identify decision-making points where you’ll stop and evaluate your progress, considering if any changes need to be made to your plans. This includes always having alternative options available and understanding your limits.

- Go into any adventure with the mindset that you may have to change your plans along the way and be prepared to accept that turning around is ok.

- Check warnings and alerts and act on the advice given by authorities.

- Talk with others who have local knowledge about your adventure. Seriously consider the advice you’re given and don’t dismiss it as not relevant to you without careful consideration.

- Check the most recent weather forecast, and re-check up to the point of leaving as this can change. Make sure you understand what this will mean for you, if you don’t know then seek advice from others who do.

- Take sufficient supplies, including waterproof clothing, at all times of the year. In winter or when snow conditions may exist this should also extend to waterproof pants and snow gaiters.

- Be prepared for the fact you may not make your intended destination. Carry an emergency shelter, spare warm clothing, emergency communication device and appropriate food.

Resources:

- Coronial findings for Ondrej Petr including Mountain Safety Council recommendations here

- https://www.police.govt.nz/news/release/routeburn-track-rescue-statement-pavlina-pizova

- https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/83536051/tramper-missing-presumed-dead-on-routeburn-track

- https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/83697672/czech-tramper-pavlina-pizova-heading-home-thanks-rescuers?rm=a

- https://www.stuff.co.nz/the-press/news/83646977/czech-tramper-pavlina-pizova-familiar-with-death-on-the-mountains?rm=a

- https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/fatal-ordeal-on-routeburn-track-the-alpine-mishap-that-killed-czech-tramper-ondrej-petr/P34MLTDM5IFIJIGXWRZO3JQMNY

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/aug/26/czech-tourist-reveals-how-she-survived-30-day-ordeal-in-new-zealand-mountains

- http://hamiltonsar.volunteerrescue.org/node/732

- https://www.1news.co.nz/2019/09/02/czech-couples-poor-planning-for-routeburn-track-hike-led-to-mans-death-coroner-finds

Tramping Rescue Story: Right Place, Right Time

July 1985, Routeburn Track, retold by my parents Keith and Susan Milne

Pavlina and Ondrej’s story sent chills down my spine, because it was so reminiscent of a story that I’ve heard my parents tell countless times. Over 30 years earlier, at a similar time of year and almost the exact same location, a German couple almost died on their way to Mackenzie Hut.

Lake Mackenzie Hut

My parents are both avid trampers, Dad from a young age, and Mum from her time with the Otago University Tramping Club. Once they’d moved back to Dad’s family farm, they were involved in setting up a local tramping club in western Southland. This club would often plan a winter tramping trip and in 1985, that winter trip was to Lake Mackenzie Hut on the Routeburn Track, walking in / out from the Divide.

There were snowstorms and then a thaw with avalanche activity prior to the trip, but the weekend had a clear weather forecast. The group consisted of four adults including my parents, and two older teenagers.

The group walked in to Mackenzie Hut from the Divide with no issues (not including the kea dumping snow down their necks, but that’s another story).

It was about 6.30pm and Mum was sitting outside on the porch cleaning her teeth, when she spotted two torches coming into view high above on the track around the Ocean Peak corner.

Mum kept an eye on the lights, and within a few minutes watched with growing concern as they separated, going in opposite directions and getting further apart. She went back inside and told the rest of the group what she’d seen. She was concerned that the people could see the lights of the hut and were coming straight for it, not knowing about bluffs, boulder field and a frozen lake that lay in their path.

The Rescue

The three men grabbed warm gear, food, water, a first aid kit, and a survival bag. Mum and the two teenagers stayed in the hut, stoking the fire, and preparing hot food and drinks.

The three guys raced up the track as fast as they could. They came across a man first, a German tourist in his early 20s. He wasn’t making much sense and was off the track, partway down an avalanche chute. They took him back to the track and moved him to a safer location by the bush-edge. One of the men stayed with him, while the other two rushed back to find his girlfriend.

They found her further down the avalanche chute. She was making even less sense and seemed drunk. One of her feet was completely bare in the snow, but she wasn’t even aware that she’d lost her shoe, let alone her sock. The two men carried her on their backs up the track.

They left her pack (and her shoe which hadn’t turned up) in a safe spot behind a tree, and took turns carrying her on their backs down the track. Her partner was with it enough to follow the men, still carrying his pack.

Back at Mackenzie Hut, one of the teenagers had broken into the warden’s hut to see whether there were any emergency supplies, including an operational radio to raise the alarm if needed. There was no way to call for help, but there was more food.

The men and the German couple made it back to the hut by 9pm. Mum and the teenagers fed them with warm food and drinks. The group put the woman into two sleeping bags zipped together with mum and one of the teenagers to warm her up.

The Recovery

The next day the group decided that the German couple weren’t in a state to walk out. But they were lucid, and could explain how they came to be in this situation.

They were very fit and were studying Physical Education at university back home in Germany. This was their “summer” holiday, to wintery New Zealand. In Queenstown they’d checked and were told there was little snow on the track. This information was echoed by locals in Glenorchy. The couple had tried to seek information from DOC in Glenorchy before embarking on the trip, but DOC was closed over the weekends back then.

The couple set off to Routeburn Falls Hut on Friday, where they stayed the night. They didn’t have tramping boots and wore travelling clothes likes jeans and cotton. On Saturday, they climbed up towards Harris Saddle, joined by three local Queenstown trampers, who were planning on returning back down to Falls Hut. They reached Harris Saddle at about 2.30pm, trudging the last hour or so through deep snow.

When the group reached Harris Saddle, the German couple asked the Queenstown locals’ opinion on whether they should continue on to Lake Mackenzie or turn back. My mum doesn’t think there were any signs at Harris Saddle back then marking times or distances. The Queenstown trampers told the couple that “the hardest part is behind you”, so despite it being late in the day, with deep snow and poor equipment, they decided to push on. The Queenstown trampers returned back down to Falls Hut.

Hypothermic

After the saddle the snow was up to the woman’s hips in the gullies. By the time they reached Ocean Peak corner and looked down at the lights from the hut, it had been dark for hours and they were both suffering from hypothermia. In their confused state, they’d argued over where to go – straight down towards the hut, or follow the track (which looks as though it veers away from the hut at this point, avoiding bluffs directly below). This is when they split up.

The couple were extremely grateful for the group’s rescue. If my parents’ group hadn’t been at Mackenzie Hut, who knows what would have happened.

Overnight it snowed again. The next day the men from my parents’ group went back up to retrieve the woman’s pack, and found her shoe, not far off the track. She must have not been barefoot for too long before the rescue. They never did find her sock. In her pack were warmer clothes that the couple hadn’t put on the day before in their hypothermic state.

The Walk Out

The walk out the next day was uneventful, although the woman’s feet were very tender, probably from frostnip. Just before Howden Hut (which has since been destroyed by a mudslide), they were met by DOC staff who had been alerted by the Queenstown locals, who had alerted police to their concerns after they’d walked out on Sunday.

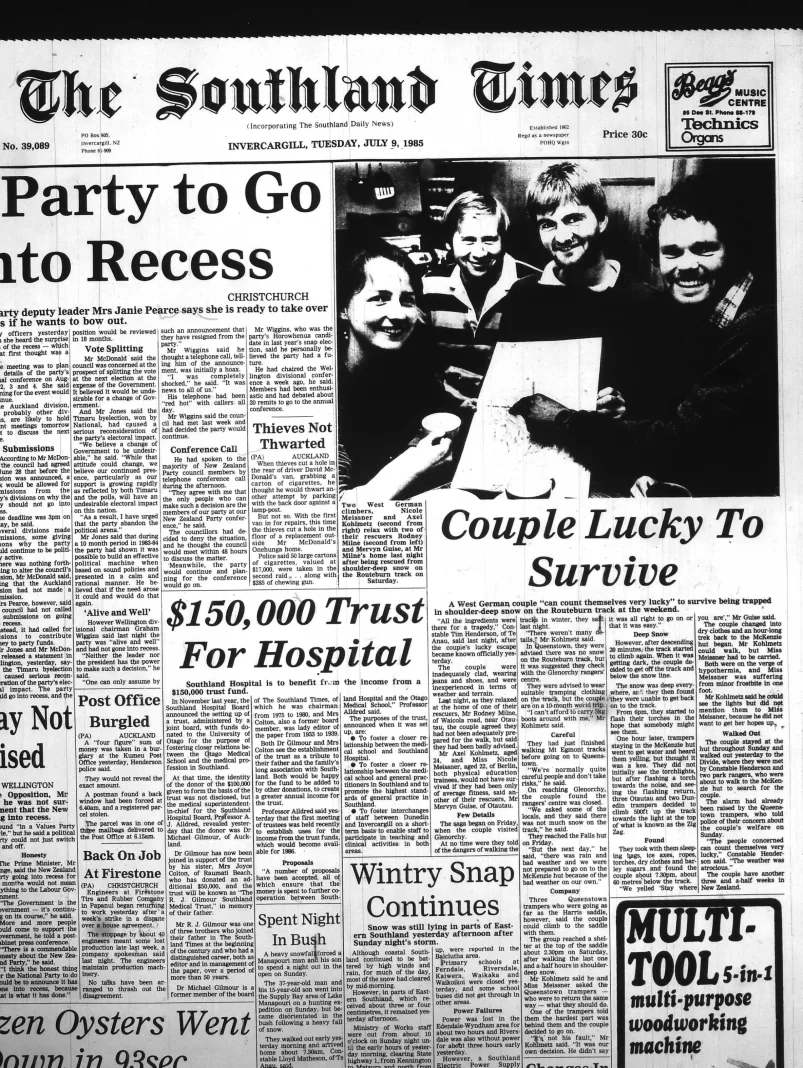

The group reached the Divide with no other drama. The German couple stayed at my uncle’s house for a couple of nights to recover physically and mentally, before setting off on their next adventure. Because this was before the age of the internet, my parents lost touch and now don’t even remember their names. I had to trawl through many months of The Southland Times papers before I found the article that mentioned the incident. The couple’s names were Alex Kohlmetz (24) and Nicole Meissner (22).

Sources:

- Verbal account by Keith and Susan Milne

- The Southland Times article titled “Couple Lucky to Survive” published front page Tuesday July 9 1985, No. 39,089

How to treat hypothermia

Prevention is best for hypothermia – having adequate gear, being aware of the weather forecast and dressing appropriately (or choosing an appropriate adventure), and making sure you’re eating regularly and adequately hydrated.

If a person is showing signs of hypothermia (mild hypothermia includes shivering, clumsiness, slurred speech, pale skin, exhaustion, fatigue) then take the affected person out of the cold / rain / wind. If that’s not possible, shelter them as much as you can – use an emergency blanket to insulate from the ground, and make sure their head is covered.

Remove any wet clothing and get them dry. Wrap them in warm clothes, blankets, sleeping bags. You can use your own body heat to help gently warm them. Give the person warm, sweet drinks (like hot Raro) and warm food.

Resources:

- https://issuu.com/nzmountainsafetycouncil/docs/hypothermia_manual_24_watermark

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/first-aid/first-aid-hypothermia/basics/art-20056624

- https://www.stjohn.org.nz/First-Aid/First-Aid-Library/Immediate-First-Aid1/Environmental-Conditions/

- https://mra.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/2015FallMeridian.pdf

Thanks for reading this rescue story (one of hopefully many!). If you have a rescue story of your own that you’d like to share, then please get in contact either via Instagram or my email. Or if you have any feedback then please comment below or reach out!

Such a fascinating and horrifying read! I can just imagine the sick feeling they likely had when things started to go wrong and they wished they could turn back time and choose differently. Thank you for your efforts in researching and writing up these stories!

Yeah it’s a pretty harrowing story, definitely a lot of learnings people can take away from it.

Awesome. I listen to a couple of podcasts that share survival stories from overseas. ‘Off The Trails’ and ‘National Park After Dark’. I will be back to read more of your stories. Such important learnings to take from experiences like these. Thank you

Thanks Alice! I’ll have to check them out. Have you listened to Real Survival Stories? It’s a similar podcast that you might like 🙂